Woman held captive in woods details experience 30 years on

Mina Kerr-Lazenby,

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

“Why isn’t anybody looking for you? Doesn’t anybody care that you’re missing?”

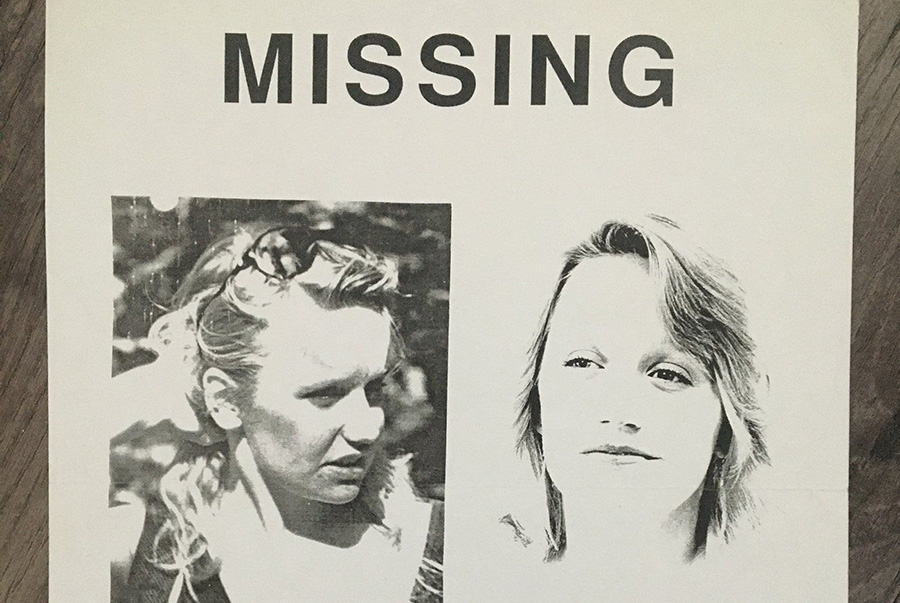

It was Day 3 of captivity for 21-year-old Lenore Rattray. Since being kidnapped at gunpoint less than 72 hours earlier, she had been berated, beaten and sexually abused. Her clothes were gone, her stomach was empty, and the makeshift camp where she was being held hostage in North Vancouver’s Mosquito Creek forest was filthy and far away from home.

The questions posed by her captor were designed to provoke, but Rattray refused to rise to the bait. She knew her family and friends were looking for her, and she was certain she would make it out of what she had dubbed “camp hell” alive.

It’s been 32 years since Rattray was taken from her workplace in East Vancouver, walked at gunpoint across the Ironworkers Memorial Second Narrows Crossing and held captive for eight days by wanted murderer David Snow.

Only now, after more than three decades of remaining silent on her experience, is Rattray ready to share what occurred during that summer of 1992.

With eight-part podcast Stand Up Eight, Rattray steps away from the traditional true crime format and offers listeners a rare first-person retelling. Holding the creative power ensured the story remained centred around what was really important to her, she says: her own life and survival, not her captor.

“My storytelling here is about what it takes to survive,” she says.

Rattray describes how each episode is themed to somewhat nebulous but relatable traits that are found in everyone, all which were relied upon to cement her own survival.

“We start with naivety, we move onto compliance, we go through adaptability, and we talk about human connection,” she says. “That then lends itself to the bigger question, of what it is that keeps us moving forward when we’re faced with a challenge.”

Snow, who was later convicted of double murder among a profusion of other criminal offences, is rarely even mentioned by name. Instead, she refers to him as “the bad guy.”

Throughout the podcast, Rattray touches on the sexual assaults only briefly. Discussing the specifics would be going into gratuitous detail, she says. Anything more would give power to her violator.

She is conscious, especially at a time when true crime is clamoured for and ranked for its shock factor, of resisting the urge to make the podcast too salacious. Created primarily as a therapeutic tool for her own recovery, and to help others, the podcast’s prime purpose isn’t to entertain with exaggerated details of the worst parts of her ordeal.

Retelling her experience honestly and accurately, she includes the parts that likely would have been overlooked if it had been sensationalized for another podcast or for television. There are moments of human connection, for example, that would never have aligned with the traditional portrayal of a cold-blooded villain or monster.

On that third day of captivity, when Snow had questioned his prisoner on whether anyone cared enough to search for her, Snow had been perusing the newspapers. It sparked a discussion about journalism, Rattray’s field of study at the time, which in turn enticed conversation about their personal lives.

Snow interspersed facets of truth with far-fetched and fictitious stories, pairing true tales of his time as an antiques dealer with those about a fabricated wife. Rattray talked about anything she could to keep him engaged: school, friends, hobbies.

“It was horrific. It was horrible. It was every bad thing you can imagine happening to a person, but with a twist in the sense that there was a weird human connection,” she says. “Our time together evolved into conversations about my career aspirations. He had some stolen photography equipment, and I gave him a lesson on photography. He shared about his life and I shared about mine, we read the newspaper, he made sure I had contact lens solution. Those are the kinds of things that you don’t see in true crime.”

Eight days after carrying out Rattray’s kidnap, Snow was caught by police when he tried to abduct another woman. Having killed a couple in Ontario two weeks before embarking on a kidnapping and sexual assault spree, police in Toronto and Vancouver had already long been searching for him. Rattray was found by North Vancouver RCMP officers, hogtied in the woods.

Rattray says her level of trust has been “greatly impacted,” and every day she lives in fear due to her experience. “When you go through something like that, you’re on a different level of alert than you would have been before, forever,” she says.

There is residual anger as Rattray tells her story now – each episode of the podcast is peppered with expletives. She acknowledges the risk that comes with reopening old wounds more than three decades later, but is quick to point out those wounds never truly healed to begin with. Putting the podcast together has been the cathartic experience she needed, she says.

Even the podcast’s launch was held at The Raven pub in Deep Cove, a mere glance away from the Mount Seymour woods where she was found by police. It was chosen specifically, she says, to show she isn’t afraid to revisit her past.

“There’s a power in where that event was chosen, because I wanted something that was near Mount Seymour,” she says. “To me, the messaging, symbolically, is that I’m in control here. I’m still in control.”

Stand Up Eight is available in full via Spotify and Apple.

Mina Kerr-Lazenby is the North Shore News’ Indigenous and civic affairs reporter. This reporting beat is made possible by the Local Journalism Initiative.